If you pay for a cup of coffee, you enjoy the warmth and taste in the moment and benefit from the caffeine kick a few hours later. If you pay for health insurance, you benefit from it two years later when you need your routine exam. If you pay for a customer, you don't benefit from the acquisition until the customer's subscription revenue exceeds their cost of acquisition.

Each customer acquired by your SaaS company has a payback period—an amount of time that it will take for the customer to pay back their cost of acquisition. The shorter the payback period, the faster your company can grow. You don't need a financial analyst to calculate it!

Think of each customer you pay to acquire as an initial investment. You're banking on the fact that this initial investment can at least come to a break-even point and hopefully produce positive cash flows in the future. If you don't know how each acquisition affects your net cash flow, you're sailing in a SaaS sea with no sails. Getting your payback period method down may be the best way to understand how much you can spend on each customer.

Your payback period determines the efficiency of your acquisition model, and it's too important to be muddled or misunderstood. We're going to dive deep on how to calculate and reduce longer payback periods so you can maximize efficiency and growth in your SaaS company.

What is a payback period?

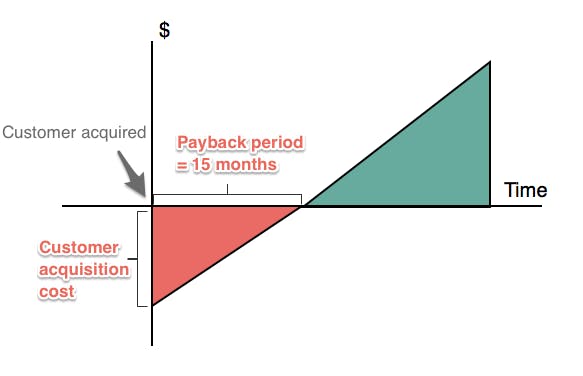

The payback period in capital budgeting is the amount of time it takes for your company to recover the cost of acquiring one customer. For example, a customer that costs $350 to acquire and contributes $25/month, or $300/year, has a payback period of 13.9 months. As time increases, a customer pays back more of the costs it took to acquire them in the first place – their customer acquisition cost (CAC) – through their incremental subscription payments.

The example in the graph above shows revenue/spend on they-axis and time on thex-axis.

The time before the company earns back the CAC is shown in red. Eventually, the customer pays back all of their CAC, shown here when the line crossed the x-axis. Once the cost of the investment is covered, then the customer's payment can go toward the company's growth. That time period is shown in green. In this example, it takes 15 months for the company to regain the original investment in CAC.

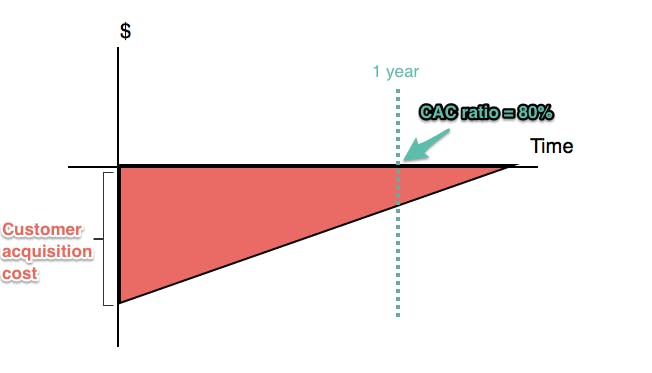

The inverse of the payback period is the CAC ratio, or the percentage of sales and marketing spend used to acquired a customer that will be gained back within a year of the customer's acquisition.

In the example above, the customer pays back their CAC over time, but the time to payback CAC exceeds one year. One year after the customer's acquisition is marked by the green dotted line. At this point, 80% of the CAC is paid back, meaning the CAC ratio is 80%.

Why is it important to calculate your payback period?

The payback period shows you the efficiency of your acquisition strategies. The shorter your payback period, the more financially efficient your acquisition methods are. You need to understand acquisition efficiency to understand how acquiring different types of customers affects your corporate finances and how sustainable your investment decision are and current strategies are in the long term. Keeping a consistently growing annual cash inflow should be your target for the end of year from the start: the more accurate your payback method is, the quicker you'll have money to start reinvesting.

Longer-than-ideal payback periods will tell you that you need to make improvements in the areas that affect the payback period. The length of your payback period is dependent on:

- Customer acquisition costs: Subscription-based companies assume the risk of paying CAC upfront and replenishing that spend as the customer pays ratably over time. The greater the initial cost of customer acquisition, the longer it will take to pay it back bit by bit over time.

- Customer monetization: The size of the increments in which customers pay back their CAC each month (or each year) depends on how you monetize your customers. You may charge them one flat rate, create individualized plans, or scale their pricing according to usage on a value metric. The payment plans that you create for your customers influences the length of the payback period.

Improving any and all of these factors will help you earn back CAC faster, at which point you'll have future cash flow to invest back into your company and grow.

What is the average SaaS payback period?

SaaS startups average a 5-12 month CAC payback period. Efficient companies are closer to 5 months (or less), while companies lower-performing companies are closer to the 12 month timeframe for payback.

How do you break down the variables used to calculate payback period?

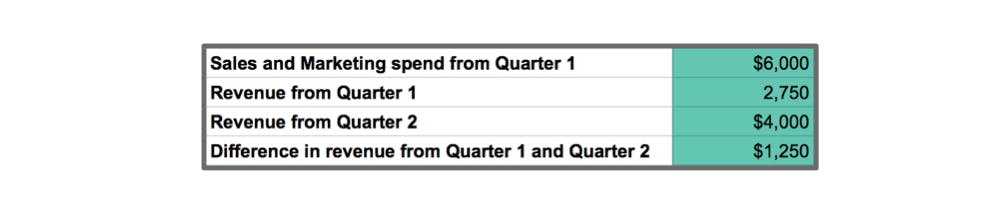

The sales and marketing spend for Quarter 1 includes all of the costs to acquire the new customers for Quarter 2. The difference in subscription revenue between the two quarters is the amount of new revenue that the acquired customers added in Quarter 2.

For example, imagine the total sales and marketing spend (including paid acquisition, marketing campaigns, and salaries of sales and marketing team members) totals $6,000 for Quarter 1. The revenue from Quarter 1 is $2,750, and the revenue from Quarter 2 is $4,000.

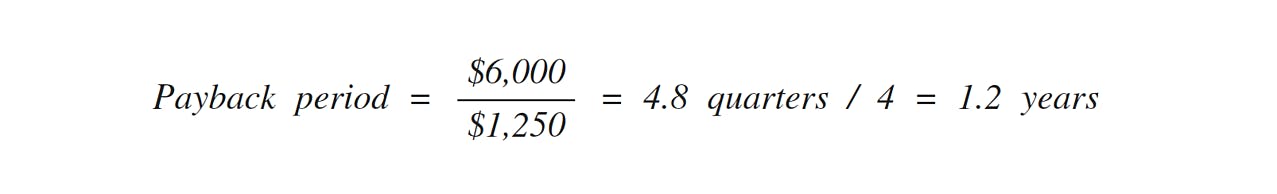

The payback period is the sales and marketing spend from Quarter 1 ($6,000) divided by the difference in revenue from Quarter 1 to Quarter 2 ($1,250).

The payback period is 4.8 quarters, or 1.2 years.

To find the CAC ratio, or determine how much of the sales and marketing spend is recovered in 1 year, invert the equation to divide the difference in subscription revenues between the two quarters by sales and marketing spend from the previous quarter. This tells you how much spend will be recovered in one quarter. Multiply by 4 to find the spend that will be paid back in one year.

The CAC ratio is 83%, meaning this SaaS company will recover 83% of their customer acquisition cost to acquire those Quarter 2 customers within one year.

An implicit variable is the type of acquired customer that you are considering in your calculation. While you can calculate an average of the payback period for all of your customers, you'll end up with a number somewhere between the shortest and longest payback periods (for the most and least efficient acquisitions, respectively). This gives you a general snapshot of your acquisition strategy but doesn't provide direction for improvement. You'll need to find the most effective way to use your free cash flow.

Instead, calculate payback periods for different types of customers that you acquire through different acquisition channels and monetize with different models. You may have the following types of customers within your customer base—groups that are more or less expensive to acquire than others and are monetized differently:

- High volume, low contract value customers that you acquire rapidly at low cost

- Low volume, enterprise-level customers with high contract values, longer sales cycles, and higher cost of acquisition

- Freemium customers that were acquired with marketing spend, don't contribute to your revenue, and have the potential to upgrade to a paid plan

Your payback period—and therefore acquisition efficiency—for each group of customers may be different, and your strategies for improving enterprise acquisition and investment opportunities will be very different from those for improving freemium acquisition. Breaking down the payback period beyond the average for all of your customers will help you shape different ways to make acquisition more efficient.

Issues with calculating payback period and how to overcome them

Critics of the payback period metric will level a range of charges at its door. Here we look at some of them, and how to adjust your calculations accordingly.

1. It is too general

Typically, payback period is calculated across a whole business, by totaling all customer acquisition costs in a period, and dividing by revenue contributed by new customers for the following period.

For example, if marketing costs for January were $18,000 and revenue generated by new customers in February was $2,000. It will take those new customers 9 months to cover the cost of their acquisition.

$18,000 / $2,000 = 9 months

But this doesn’t tell you enough. For example, there may be some marketing channels that produce more profitable customers, faster. You’ll want to double-down on these. Or you may have extremes of customers - from those who join at a heavily discounted price, to those who cost relatively more but that are likely to stay for longer. By aggregating them all together, you can skew the calculation and get a misleading measurement.

How to overcome: The answer is to segment your costs and customers, according to what makes sense to your business.

2. It doesn’t account for churn

Using the example above, what happens if some of those new customers churn before 9 months? The cost of acquisition has already been sunk and so will remain the same, but the revenue side of the equation will be reduced. As a result, the payback period will increase; but for customers who remain, the payback period will have been unaffected (all other things being equal).

How to overcome: One approach is to strip out customers who churn and calculate the loss from them separately.

3. It presumes ongoing profitability

It becomes more misleading when customers churn or downgrade after their payback period. The payback period presumes that once customers become profitable, they stay profitable - but SaaS businesses know that is far from reality.

How to overcome: The answer is to be clear about what payback period is illustrating, and not be tempted to use it to make long term revenue and profit projections.

4. It ignores upgrades (sometimes)

What type of revenue you include makes a difference to the payback period. If you only count revenue from the initial subscription and miss extra revenue from upgrades or price increases generated during the payback period, then you’ll be understating the payback period. And at what moment do you stop recognizing new revenue - at the exact point a customer reaches their acquisition cost (to the dollar and cents), or do you include everything in the time period you are measuring?

How to overcome: The answer is to have clear definitions in place of how you are going to define revenue for the purposes of calculating payback period; and the analytical systems that allow you to pull the data accurately.

5. What counts as a cost?

Some acquisition costs are obvious, such as advertising and marketing spend. Some are less so - for example press coverage, hackathon events and how you support your current customers all feed into your brand reputation. In theory, payback period should include all customer acquisition costs, not just the direct ones. But attributing an activity to a customer acquisition is easier said than done.

How to overcome: Though accuracy is important, consistency is more so as it allows you to compare payback period over time.

6. It is ambiguous about who to include

You need to be clear about what constitutes a new customer. Is it fair to include extra users in existing accounts, where there may have been very little, if any, acquisition cost? Also should you treat the cost and revenue of returning customers in the same way as brand new ones?

How to overcome: Again, the answer is to have clear definitions in place, to ensure you are measuring payback period consistently.

7. It does not account for inflation

As payback period measures cost of acquisition at a specific moment in time, that part of the calculation can be skewed by inflation. In other words, $10 last year is not worth the same as $10 this year. The problem is more profound when calculating payback over longer periods; and more so if you regularly adjust your prices for inflation.

How to overcome: The answer is to adjust the cost of acquisition in your analysis, so it remains relative.

What is a good payback period?

Most broadly speaking, a good payback period is the shortest payback period possible.

It is generally considered “healthy” for a SaaS company to have a payback period of 1 year, although it will vary throughout your company's lifetime as the various factors that contribute to the payback period fluctuate and evolve. Anything between 5-7 months considered high-performing.

Even though it's considered acceptable,12 months is a long time to recoup acquisition costs—which underscores why acquisition is a much less financially efficient growth lever than retention, expansion, and monetization.

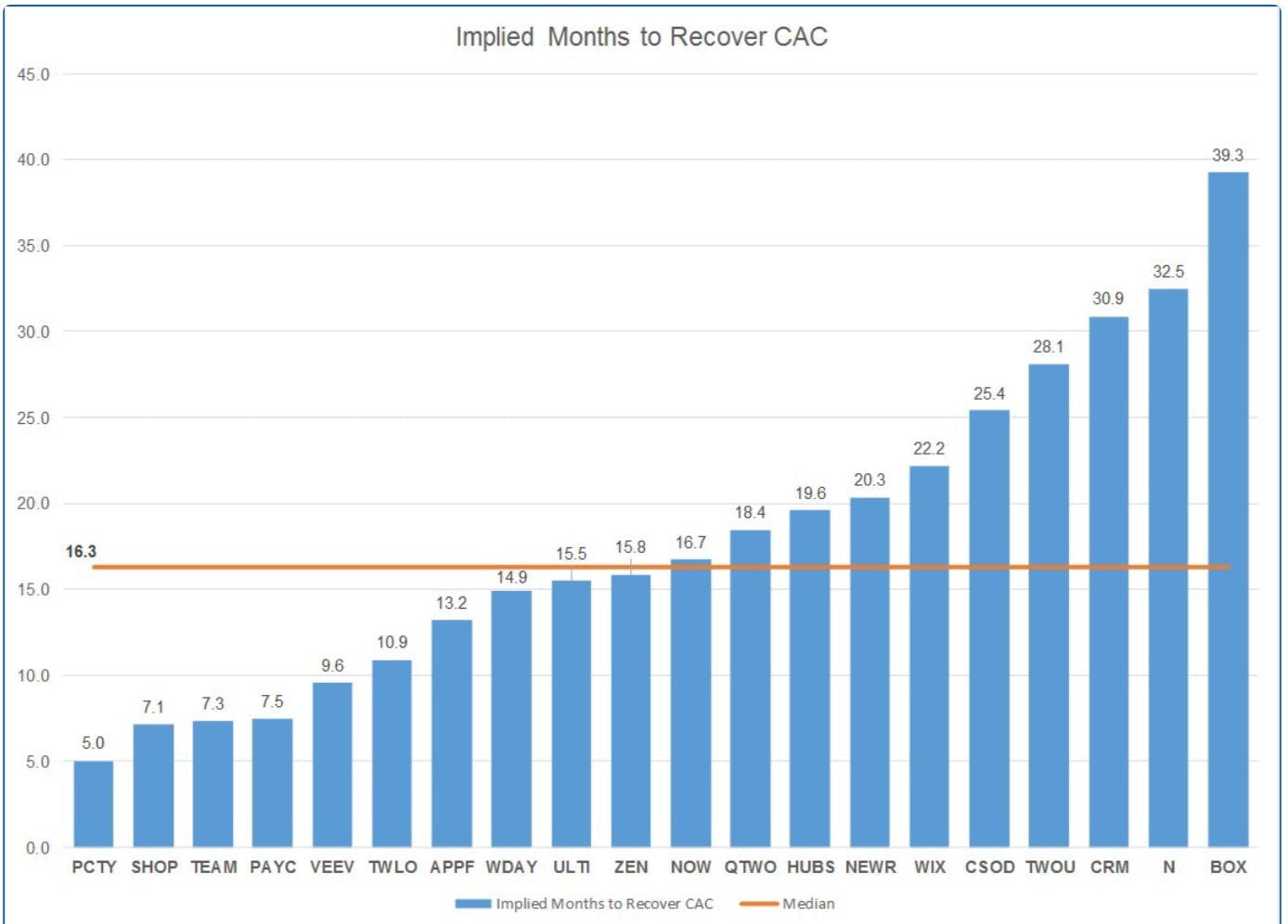

This study into payback periods of SaaS companies shows an average of around 16.3 months.

Looking at the best-performing companies in this cohort gives us clues as to how they have created a low payback period.

- Paylocity: have a network of over 30,000 brokers and generate ~30%+ of their ARR through referrals.

- Shopify: acquire most customers organically (~40% by word of mouth at their IPO and 30% through partner referrals).

- Atlassian: mostly sell directly to technical users, who collaborate on product development, with a low-friction, self-serve sales model.

- Veeva: took first-mover advantage by creating a bespoke CRM for pharma and biotech reps.

The chart also illustrates how companies with a higher payback period tend to be larger (e.g Box - $771m in annual revenue, NetSuite - $200m, Salesforce - $21bn, 2U -$575m). This is logical; with bigger pockets and more predictable revenue, they can experiment with acquisition strategies, forgoing some of the efficiency that is a must for leaner SaaS businesses.

How payback period relates to other SaaS metrics

The payback period is influenced by, and influences, some familiar SaaS metrics.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

You could argue that the whole purpose of measuring payback period is to find the optimum CAC. A high CAC will worsen the payback period (as it takes longer to pay off the investment), and vice versa.

CAC Ratio

The CAC Ratio is a more visual representation of the return you’re getting on each new customer. It is shown as the percentage of the CAC paid off by the end of the expected payback period. Ideally you’re after at least 100%, with anything less meaning the customer is taking longer than average to return a profit.

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)

Though CLV and payback period are not linked mathematically, they can be seen as subsequent stages. Payback period gets you off to a good start, and then it’s over to CLV to reap the rewards. (Read more about customer lifetime value)

Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR)

Two things impact payback period; how much a new customer costs to acquire (CAC), and how much they spend. The CAC of a customer never changes (though it can change from customer to customer), but how much they spend can. In other words, increase MRR, and see the payback period fall. But variables are two ways things, and if MRR starts to drop (MRR Churn), it’s going to take longer to turn your customers profitable.

Net Revenue Retention (NRR):

By including the value of upgrades, downgrades, and churn of customers within their payback period, you get a more accurate picture of actual revenue, and so a more accurate payback period reading. You can also use NRR rate as a proxy for payback period. If the NRR rate is above 100%, it should follow that your customers are becoming profitable sooner.

The payback period does not account for customer churn nor the time value of money. If you think of the CAC as a loan and the payback period as the loan repayment schedule, you'll still have to pay the loan even if the customer churns - without the customer's help.

Comparing the payback period for customers acquired through different channels allows you to see which channels are more profitable. You can then focus on the channels that will help your company grow.

How to reduce payback period

However you measure payback period and whatever benchmark you employ to judge success, one thing is true for all SaaS companies: reducing it is a positive. Here are four tactics that SaaS businesses can employ to reduce payback period.

1. Experiment with sales channels

The cheaper you can get customers, the faster you should get a profit from them. So it’s worth testing out new sales channels to see if you can cut the cost of acquisition. There are plenty to try. Digital tactics, like PPC, can be enabled quickly, do not require a significant upfront investment, and can be measured in real time. Others, such as SEO, traditional PR, and community creation require patience. But be careful not to analyze sales channels in terms of CAC alone. A channel with a low CAC that doesn’t produce many customers, isn’t much help. So too if the customers don’t hang around very long. So also factor in MRR, churn, and CLTV in coming up with the perfect channel mix.

2. Find the right price points

Experimenting with sales channels can take time. But changing your prices should be far easier. Clearly putting your prices up is one way to increase revenue and cut the payback period. But it’s risky too, with disgruntled customers likely to leave. It may be more palatable to change the terms of a subscription as a way to bring committed revenue in sooner. Or you could incentivize customers to pay for more of their subscription upfront.

3. Grow your base

Increasing your prices is not the only way to make more revenue from customers. Having a scaled pricing model ensures they spend more to access more of your service. Promoting technical support, training or paid-for research represent other new revenue streams. Anything that increases a customer’s spend will see their payback period reduce.

4. Cut churn

Unless you’re stripping out canceled subscriptions from your payback period calculation, then churn is going to hurt it badly. The best way to cut churn is to ensure customers don’t want to leave in the first place. And when they do, inspire them to stay by reinforcing the benefits of your product and/or offering incentives to stay.

Read our guide for more on how to calculate and reduce churn.

Secrets of companies with relatively short payback periods

Alex Clayton, an investor at Spark Capital, admits that there isn't one universal way to reduce your payback period. Rather, there are general principles that many successful companies with shorter payback periods follow:

“... A strong brand, great product and continued development, self-service and word of mouth (organic) traction has a lot to do with an efficient sales organization."

With these principles in mind, you can learn from the best techniques of the public SaaS companies with the shortest payback periods and apply them to your growing startup:

- Focus on organic acquisition, like Shopify. They've established a leadership position in a very specific market and built a network within that market. This allows for more acquisitions through referrals and word-of-mouth, which lowers sales and marketing spend.

- Use a self-service model, like Atlassian. This company has a very specific audience, and by providing the right product to meet that audience's needs, they don't need a sales team to sing the product's praises. Achieving just right product/market fit can help you save massively in sales and marketing spend.

These techniques all help you reduce your sales and marketing spend so that CAC is lower and the payback period is shorter. You can also lower the payback period by monetizing your customers better so that they pay back more of their CAC quicker. Below are some of the best techniques from SaaS companies with highly effective customer monetization:

- Consistently increase expansion revenue, like Front. When you increase the revenue a customer contributes through up-sells and cross-sells, they'll pay back their CAC quicker over time.

- Upselling customers along a value metric that aligns with usage, like Appcues. As Appcues customers grow and have a greater need for onboarding optimization, they can scale up their plans according to their volume of monthly active users.

- Iterating and experimenting with your pricing, like Intercom. There's no way to know from the get-go what prices will work best to provide the right value match for customers and make sure your company grows and runs efficiently. Don't be afraid to change your prices to find what works best.

By improving how you monetize your customers, you have the potential to increase customers' lifetime values and earn more revenue from customers at a faster rate. This means shorter payback periods and higher, faster growth potential.

Payback period FAQs

What are some limitations of using the payback period?

The three biggest limitations of using the payback period are:

- it doesn't account for the time value of money (initial cash flow has a higher value than cash flow received in later years)

- it doesn't consider a project's rate of return

- it doesn't account for the cash flow received after the payback period

What is IRR?

IRR or internal rate of return is a financial metric used to determine the profitability of certain business investments. Most broadly speaking, the higher the IRR, the more desirable the investment opportunity is. IRR is calculated using the same formula as the net present value (NPV).

What is a discounted payback period?

The discounted payback period is the procedure used to determine the profitability of a certain project or an investment. By calculating discounted payback period, you learn how many years it will take to earn profit from the initial investment.

What is discounted cash flow (DCF)?

Discounted cash flow is a valuation method used to calculate future cash flows from a particular investment.