Why do prices end in 9s?

Why do so many prices end in 9s? You can get an apple for 69 cents Or maybe a canoe for $899.99? Initially, you might only see that 8 on the left and celebrate your new $800 dollar canoe. But in reality, it’s only a penny away from $900. This feeling falls under the umbrella term of psychological pricing which takes advantage of how we recognize prices.

In a university study from 2021, it was found that retail sales increased by 60% when implementing psychological pricing. Plus, retailers who have done away with this pricing have even failed completely. It’s no wonder that software companies do it too, even titans like Zoom end their prices in 9.

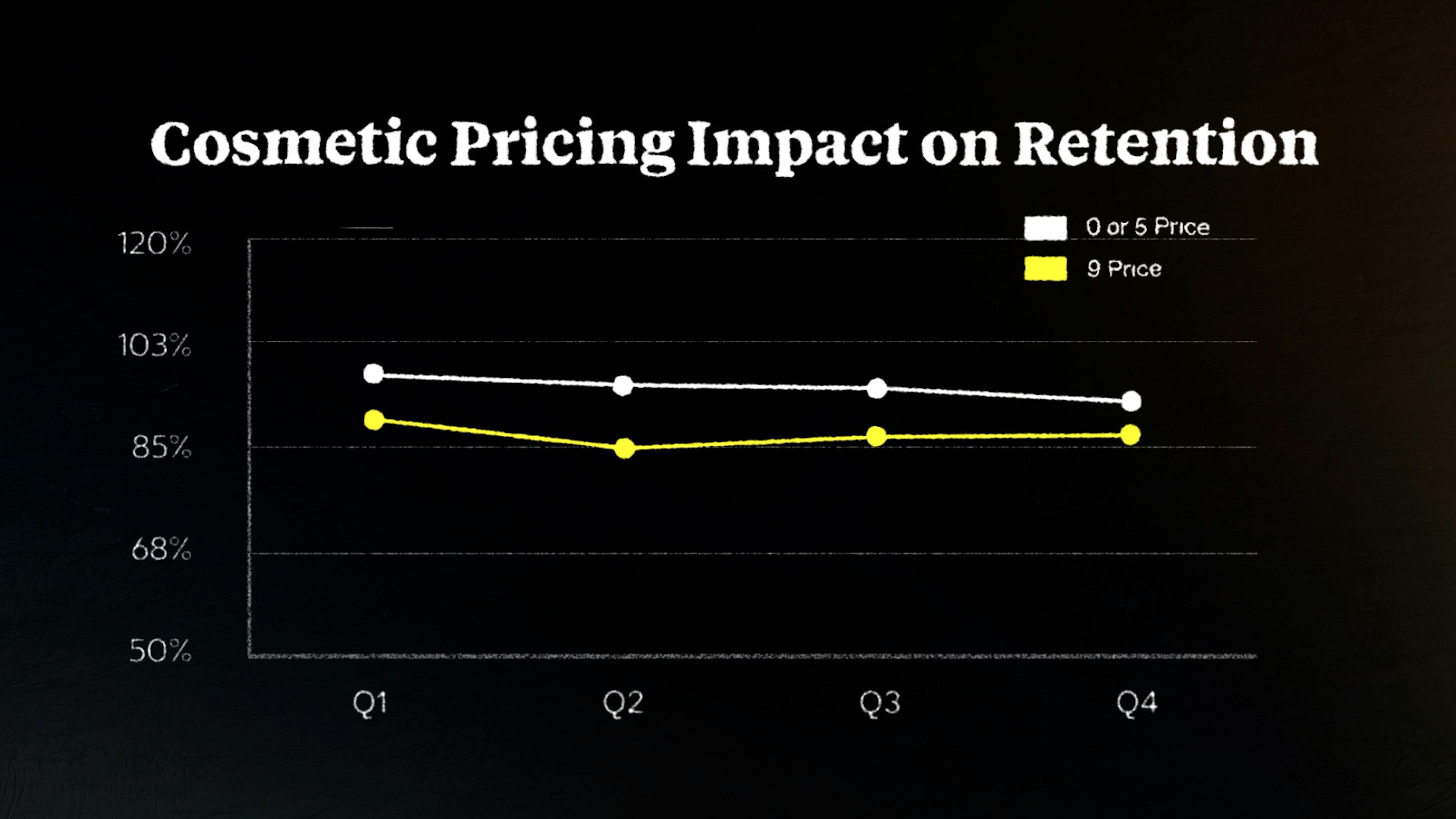

However, data shows that companies with prices that end in 9s are suffering from worse retention than those that end in 0 or 5. The only way to nurture your relationship with your customers is by providing them with consistent and long lasting value - and an honest price point is an integral part of that relationship. In order to fully understand this growth hack for what it is, let’s look at its history.

But first, if you like this kind of content and want to learn more, subscribe to get in the know when we release new episodes.

Where did 9 pricing start?

The origin of ending in 9 pricing is murky, most likely more fable than fact, but trust me, it’s a fun story. Legend has it that in 1876, Melville E. Stone was selling the first penny paper, the Chicago Daily News. Pennies weren’t widely in circulation and with no sales tax, charging on the whole dollar was much more common. There was an opportunity however, Melville was able to convince merchants that employee theft could be reduced if they lowered the price by a penny, charging 99 cents instead of a dollar. By doing so, workers would have to open the cash register for more transactions in order to make change. It worked and the Chicago Daily News began to see momentum, but then merchants began running out of pennies. Melville just went to Philadelphia, purchased a bunch of barrels of pennies front he Mint.

But, the real reasoning might not be as concrete and poetic, but it’s more likely the result of a gradual change in the early 1900s as advertising blossomed and competition grew.

By 1997, 60% of all advertising included price points with some form of price ending in a 9. But what happens when businesses try to leave the cult of 9? In 2012, JC Penney owner Ron Johnson decided to change up the retail behemoth's approach to pricing. In an effort to be more honest, JCPenney rolled out their “Everyday Price” initiative. The idea was to rally behind transparent pricing and that meant putting an end to 9s and replacing them with 0s and 5s.

The strategy flopped immediately, and JCPenney lost 3.3 million dollars within the first year of the initiative. After their sales plummeted even more the following year, Johnson announced that they were moving away from their new pricing strategy and reinstating the age-old 99s that worked for years. But the damage was already done. JCPenney never totally recovered from the pricing blunder and with COVID decimating them further, they filed for bankruptcy in 2020.

Psychological Pricing

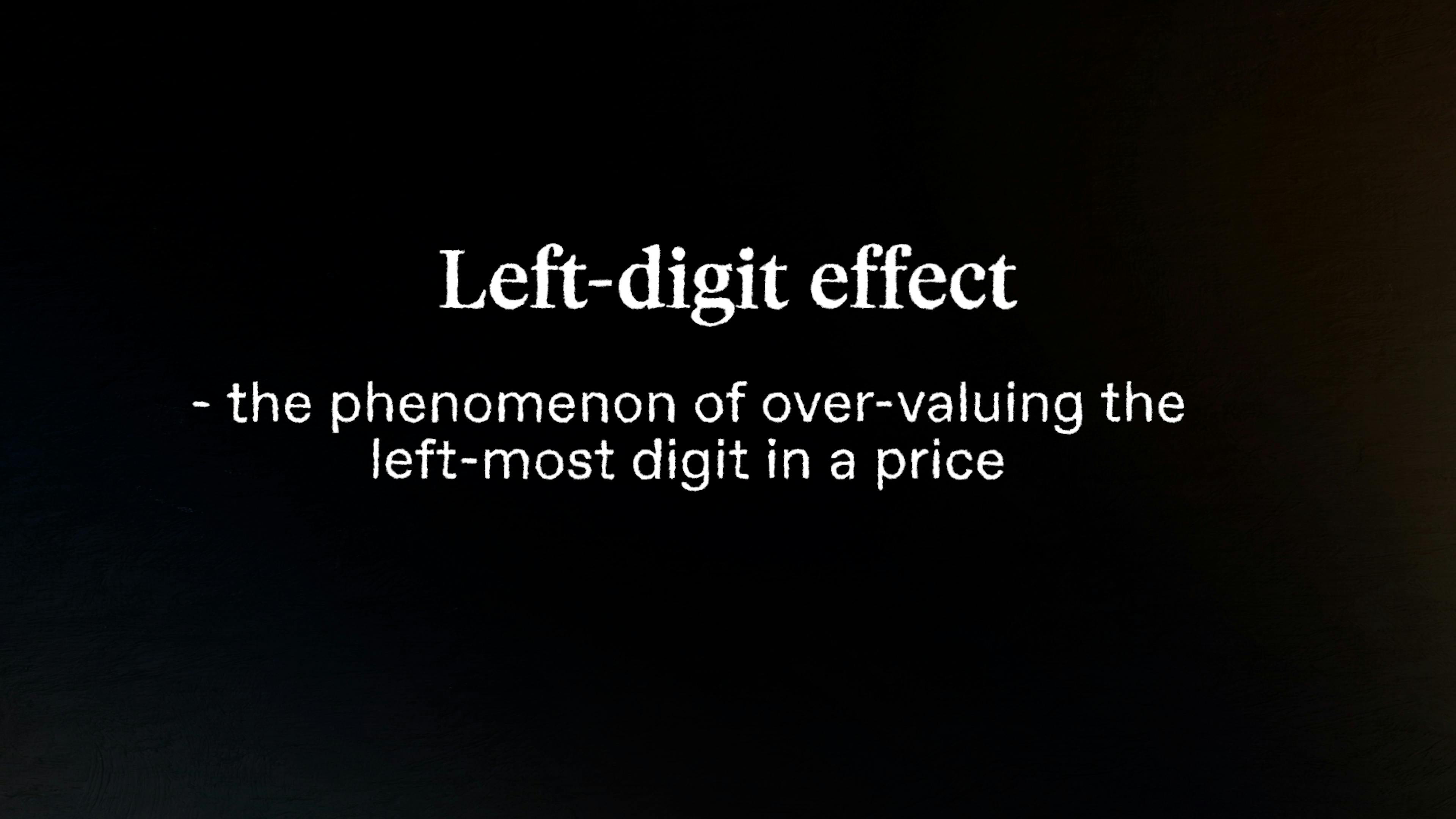

Psychologists Manoj Thomas and Vicki Morwitz proposed their theory as to why customers gravitated towards that first number. They coined the term the left-digit effect. They theorized we are overestimating the impact of the leftmost digit change in a price. Remember in the beginning when I was talking about only seeing the first number in the price of the canoe? Well me, and many other canoe enthusiasts feel like we’re getting a deal. Because it’s not actually a discount. If I show up to buy another canoe next month, I’ve already experienced the value of the product and have come to understand that the price I paid is not in fact a discount. I’m likely not going to make the same purchase again.

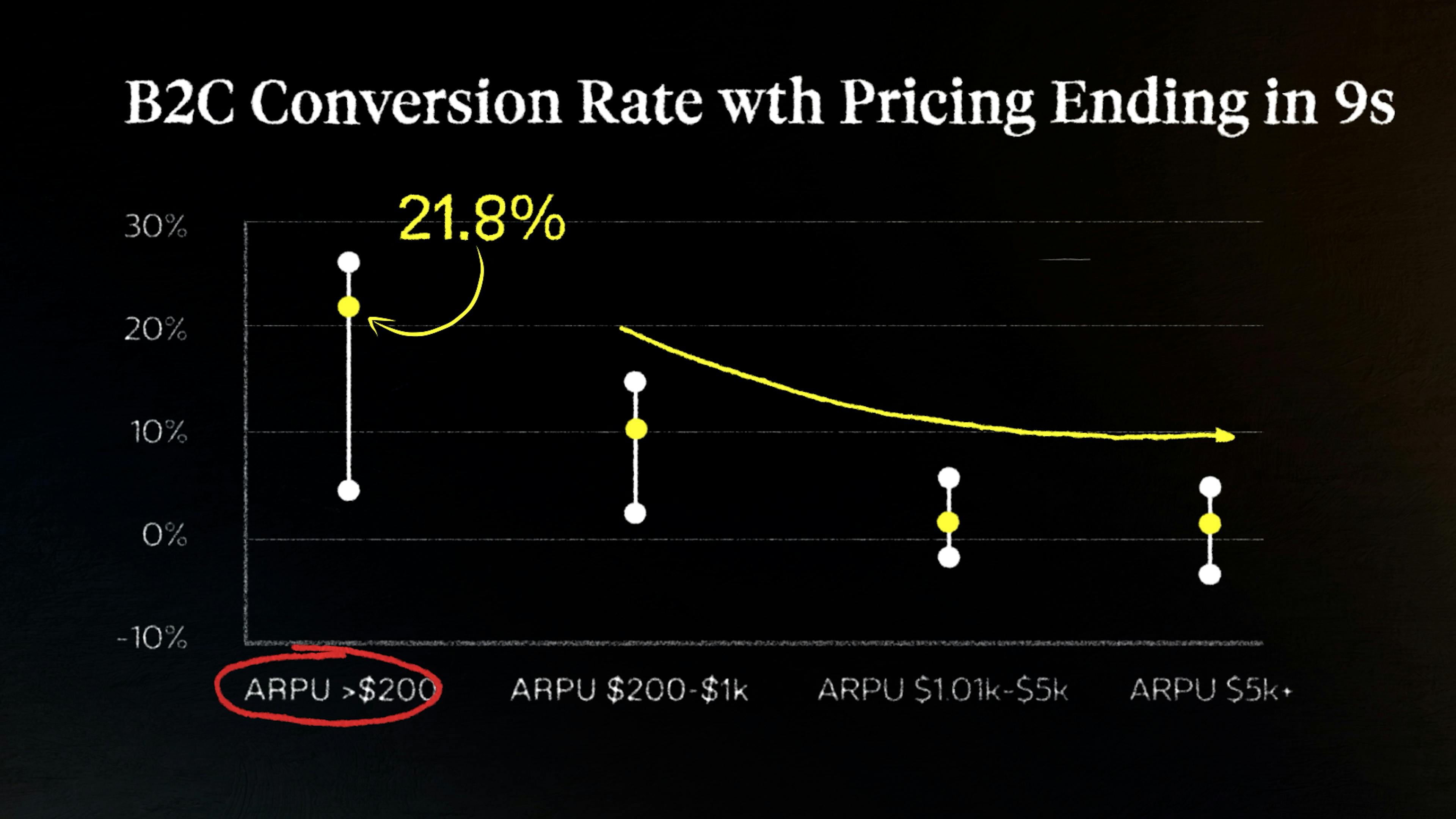

It’s a tactic that works better for products with a lower average revenue per user. We found that lower ARPU companies that priced ending in 9s had up to 22% better conversion rates than those that ended in 0s or 5s. But the higher the ARPU, the worse conversion rates became in comparison.

The reason this works for retailers is because I’m not buying a canoe every month, I may only buy one canoe one time… but with a subscription, you’ve got to deliver canoe value over and over and over again.

A subscription company needs to be focused on acquiring customers and maintaining a relationship with those customers to keep them subscribed. Value doesn’t necessarily need to keep increasing forever, but it does need to meet the expectations of that regular price point.

We have data that backs this up. In a study of over a thousand subscription companies we found that customers who converted based on a “9” price had worse retention than those who converted with a “0 or 5” price.

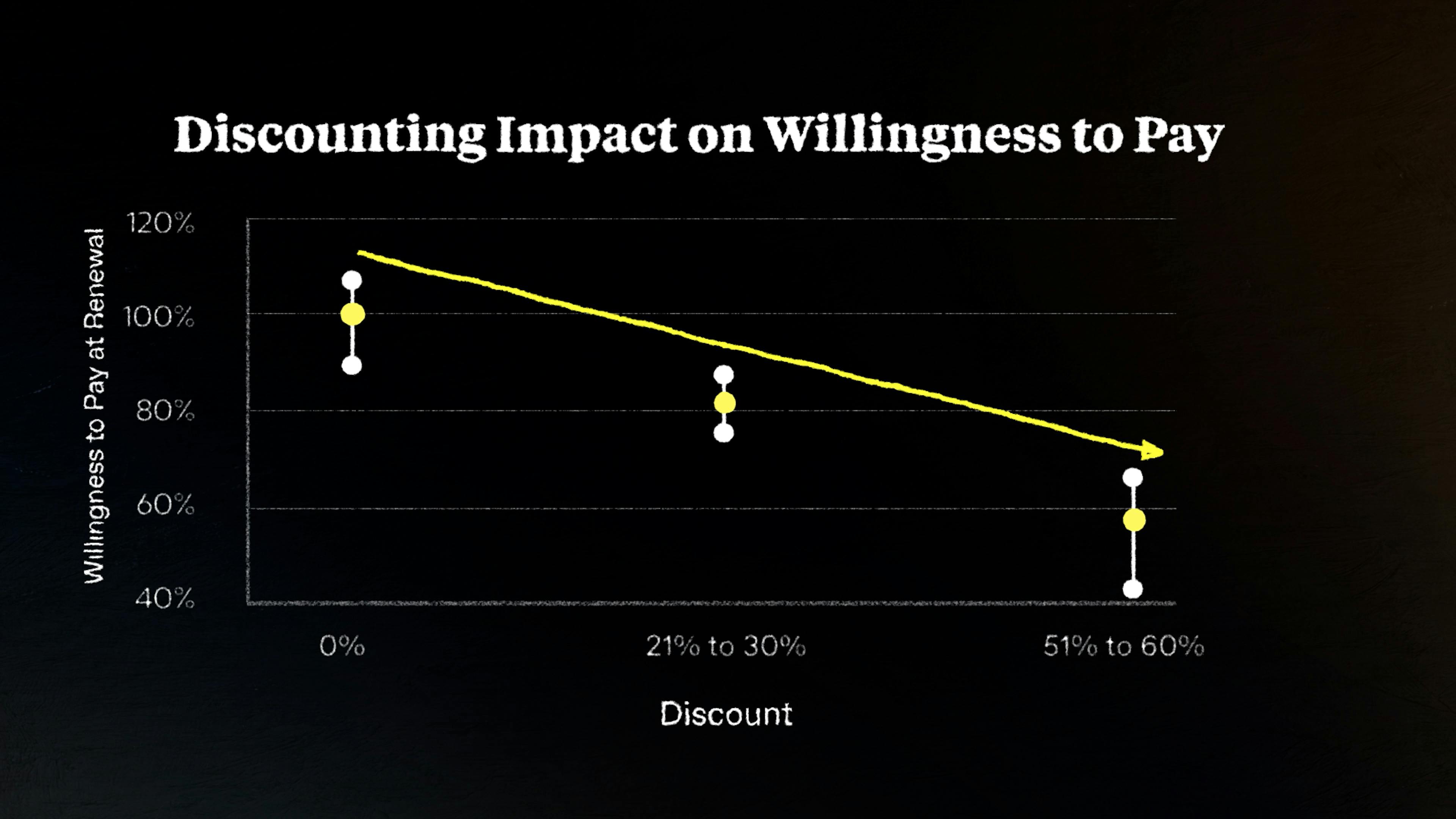

Most likely this is due to the perceived discount of the price. Going beyond just 9’s, we know that customers acquired via discounted pricing have a far higher churn rate than those who are offered no discount. When you preach a “pay-for-exactly-what-you-get” mentality and lower the price through a discount, you're lowering the value of your product in your customer’s eyes.

Value-Based Pricing

So it’s insane for me to sit here and tell you that ending your pricing in 9s is bad and you should feel bad. Clearly it is working to get folks in the door. The titans of SaaS continue to price this way and their bottom line is not shrinking. I’m underscoring its significance, not because of what it is, but because of what it isn’t. Ending your prices in 9s is not a pricing strategy.

Without a pricing strategy based on the actual value of your product you aren’t pricing on delivering what your customers want and you’re not going to lock them in for the long haul.

The only pricing strategy that does this is Value-based pricing. Value-based pricing is a strategy where you set the price of your product or service in accordance with how much your target customer base or segment believes it is worth.

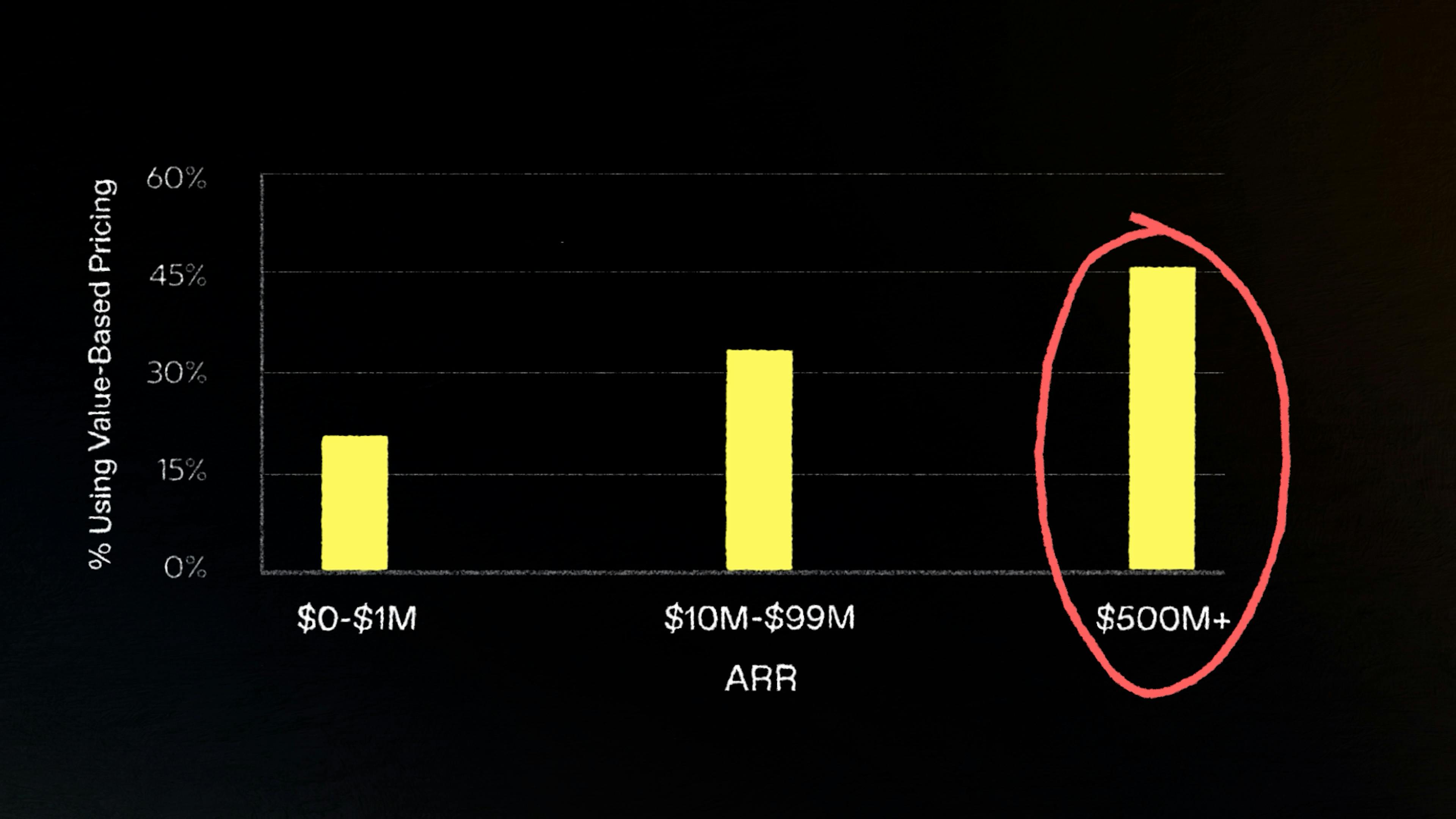

The more successful a company is, the more likely they are using value-based pricing. You can see here that 45% of companies with arr north of $500m are utilizing it compared to only 20% of companies with around $1m in arr.

Click on the image below to get all this data and more in our Pricing Strategy Guide:

Here’s a brief overview of how to price your product based on value:

At the core of value-based pricing is a value-metric. A value metric is not only how much you charge but what you’re charging for. This could be per seat, per gigabyte of storage, per canoe… alright I’ll get out of the canoe.

Next, you’re gonna want to do some research. Doing the research properly will help you avoid getting answers like “just give it to me as cheap as possible”. Start by collecting data on your customer base - who they are and what they get out of your product - and use this data to determine your price point. Asking questions like “what price would be too low that you would question the value” and “what price would be too high” can help you figure out the answer.

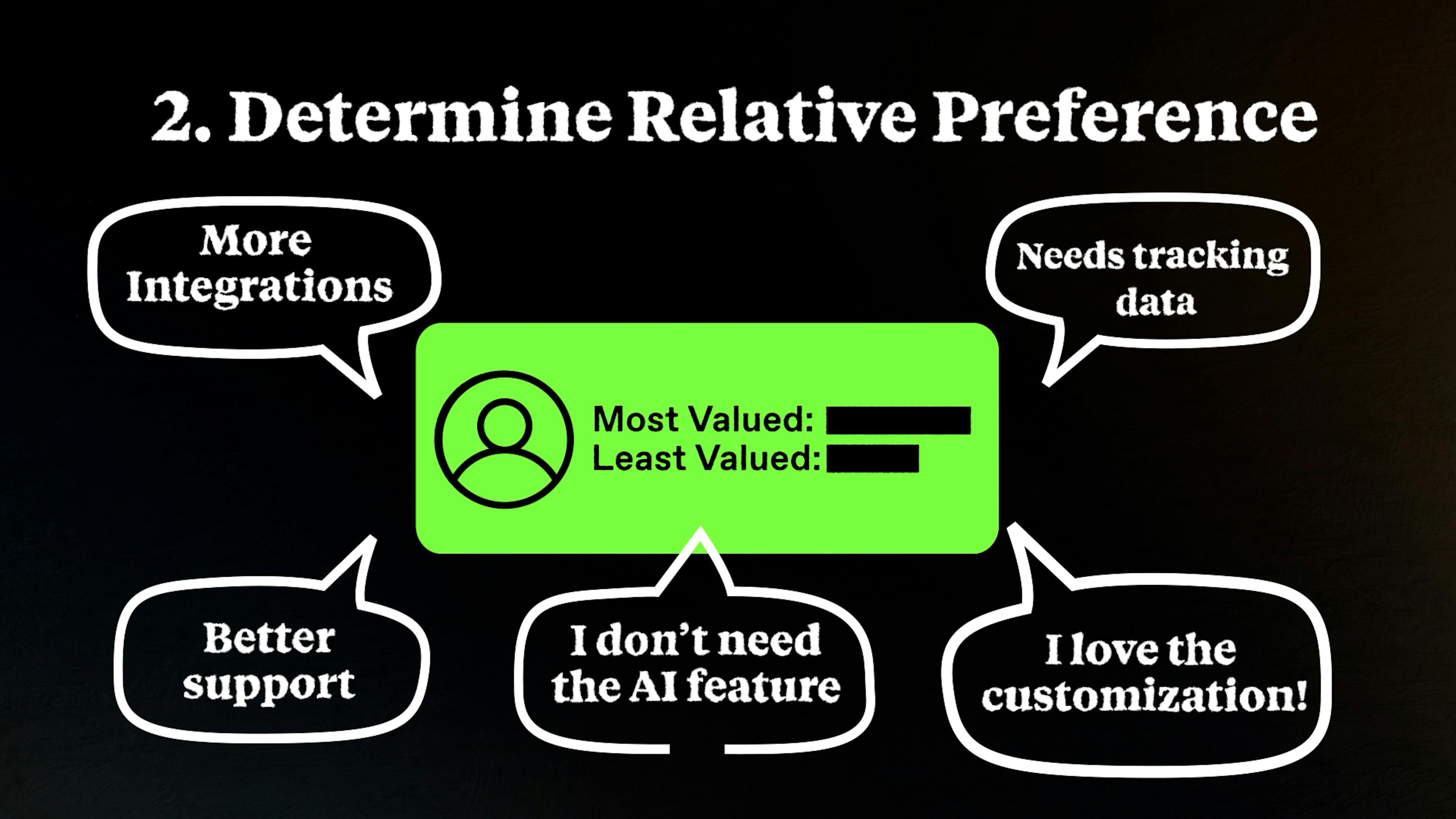

Then, figure out folks’ relative preference of what they want from a product. This is a survey that basically asks potential customers “what is the one thing you couldn’t live without and the one thing you could?”.

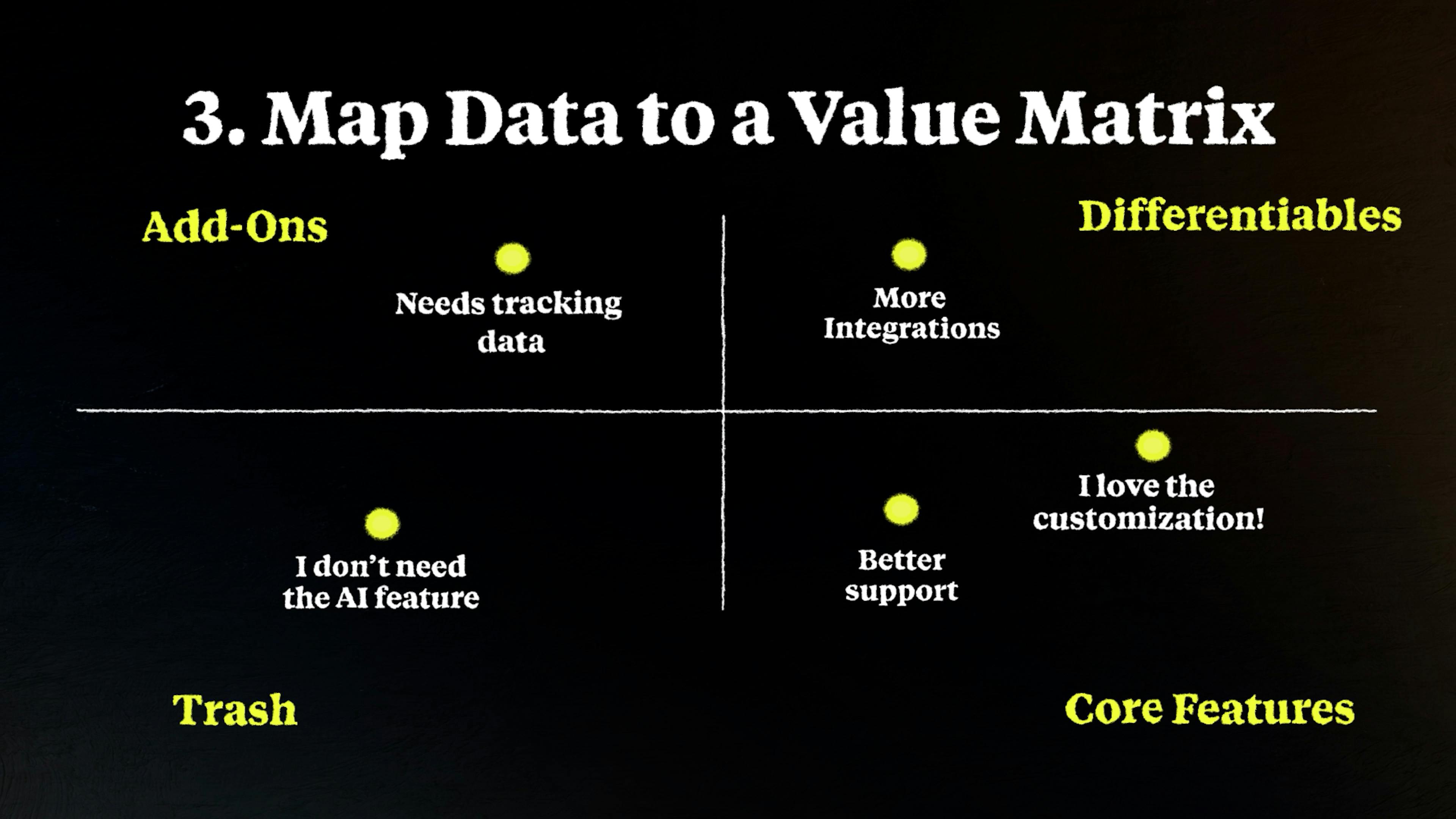

Mapping all of this data onto a value matrix will help you understand what your core features are as well those that might just be add-ons.

Once you’ve figured out value-based pricing, you’re doing more than just getting folks in the door by charming them with a 9: you're focused on retaining them through an honest exchange of value. And if you repeat this process on a quarterly basis, how customers perceive your product will be crystal clear. I’m skimming over a lot of information here about value-based pricing. The Price Intelligently team wrote a holistic guide on how to approach it so the next thing you should do is check that out to learn it all.

Subscribe to get in the know when we release new episodes.

00:00:00:00 - 00:00:29:02

Ben Hillman

Actual retail price $19.99 9 $19.99 9, 9. Why do so many prices end in nines? You can get an Apple for $0.69, or maybe even this canoe for $899.99. I know when I see this price, it takes me a second to realize the trick. Initially, I only see that number that's on the left. My brain thinks, oh, nice, a canoe for only $800.

00:00:29:04 - 00:00:49:16

Ben Hillman

But in reality, and I know you know this, it's only a penny away from $900, and this is actually closer to $1,000 once you account for other fees like tax and shipping. But here I am thinking that I got this incredible deal. This sort of pricing falls under the umbrella term of psychological pricing, which takes advantage of how we recognize prices.

00:00:49:18 - 00:01:15:01

Ben Hillman

And in a university study from 2021, it was found that retail sales increased by 60% when implementing psychological pricing. Plus, retailers who have done away with this pricing have even failed completely. But more on that in a minute. It's no wonder that software companies do it too. Even titans like zoom and their prices and nine. But there's something at play here that doesn't quite add up to a whole number.

00:01:15:03 - 00:01:42:04

Ben Hillman

It undeniably helps when you end your prices in mind with acquisition, especially in retail. But companies with prices ending in nines are suffering from worse retention than those that end in 0 or 5. So in order to fully understand this growth hack for what it is, let's look at its history. And we're going to have to go back. Legend has it that in 1876, Melville E. Stone was selling the first Penney paper, the Chicago Daily News.

00:01:42:06 - 00:02:10:01

Ben Hillman

At the time, nickel papers were all the rage, and you'd think that undercutting the price by $0.04 would win out, right? Not exactly. Pennies weren't widely in circulation, and with no sales tax, charging on the whole dollar was much more common. There was an opportunity, however, Melville was able to convince merchants that employee theft could be reduced if they lowered the price of goods by a penny, charging $0.99 instead of a dollar.

00:02:10:03 - 00:02:32:09

Ben Hillman

By doing so, workers would have to open the cash register for more transactions in order to make change. It worked, and the Chicago Daily News began to see momentum. But then merchants began running out of pennies. No worries though, Melville just went to Philadelphia and purchased a bunch of barrels of pennies from the mint directly. He solved pennies circulation himself.

00:02:32:15 - 00:02:56:09

Ben Hillman

This is one of the first rumored instances of ending prices and nines. I mean, folks figured that they might as well buy a paper since their transaction wasn't even a full dollar. They were rich. A whole penny. But the real reasoning might not be as concrete and poetic. It's much more likely the result of just a gradual change in the early 1900s, as advertising blossomed and competition grew.

00:02:56:11 - 00:03:21:13

Ben Hillman

You can actually see the change happen over time when looking at newspapers. If we start in 1919, it was still a lot more common to see prices ending in a 5 or 0. But when looking at newspapers just five years later, more nines began cropping up. And ten years after that, and so on, you get the idea. By 1997, 60% of all advertising included price points with some form of price ending in nine.

00:03:21:16 - 00:03:44:08

Ben Hillman

But what happens when businesses try to leave the cult of nine? Well, in 2012, JCPenney owner Ron Johnson decided to change up the retail behemoth's approach to pricing in an effort to be more honest, JCPenney rolled out their Everyday Price initiative. The idea was to rally behind transparent pricing, and that meant putting an end to nines and replacing them with zeros and fives.

00:03:44:10 - 00:04:09:01

Ben Hillman

Customers love honesty, right? Well, money talks and the strategy flopped immediately. JCPenney lost $3.3 million within the first year of the initiative, after their sales plummeted even more. The following year, Johnson announced that they were moving away from their new pricing strategy and reinstating the age old nine times that worked for years. But the damage was already done.

00:04:09:03 - 00:04:32:11

Ben Hillman

JCPenney never totally recovered from the pricing blunder, and with Covid decimating them even further, they filed for bankruptcy in 2020. Psychologist Manoj Thomas and Vicki Morwitz proposed their theory as to why customers gravitate towards that first number. They coined their term the left digit effect. It was their theory that we're overestimating the impact of the leftmost digit in a price.

00:04:32:13 - 00:04:56:20

Ben Hillman

Remember, in the beginning when I was talking about how I was only seeing that first number in the price of a canoe? Well, me and many other canoe enthusiasts feel like we're getting a deal. But because it's not actually a discount when I show up to buy another canoe next month, I've already experienced the value of the product, and I've come to understand that the price I paid is not, in fact, a discount.

00:04:56:22 - 00:05:20:03

Ben Hillman

I'm likely not going to make the same purchase again. We actually have some data that backs this up. It's a tactic that works better for products on the inexpensive side. We found those companies with a lower price point, that of their prices, and nines had up to 22% better conversion rates than those ending in zeros or fives. But the more expensive the product gets, the worse the conversion rates became in comparison.

00:05:20:07 - 00:05:41:05

Ben Hillman

The reason that this works for retailers is because I'm not actually buying a canoe every single month. I may only buy one canoe one time, but with the subscription, you've got to deliver canoe value over and over again. A subscription company needs to be focused on acquiring customers and then maintaining a relationship with those customers to keep them subscribed.

00:05:41:07 - 00:06:06:12

Ben Hillman

Your value doesn't necessarily need to keep increasing forever and ever exponentially, but does need to increase enough to meet the expectations of that regular price point. I mean, if you don't make any improvements to your product and why am I going to buy your product the next month? In a study of over 1000 subscription companies, we found that customers who converted based on a nine price had worse retention than those who converted with a 0 or 5 price.

00:06:06:14 - 00:06:28:10

Ben Hillman

Most likely, this is due to the perceived discount of the price going beyond just nines though, we know that customers acquired by a discounted pricing, have a far higher churn rate than those who are offered no discount. When you preach a pay for exactly what you want mentality and lower the price through a discount, you're actually lowering the value of your product in your customer's eyes.

00:06:28:12 - 00:06:45:04

Ben Hillman

So it's absolutely crazy for me to sit here and tell you that ending your pricing and nines is a bad idea, and you're bad and you should feel bad. You're not bad. You're good. You're great even. Clearly, this works to get folks in the door. And the titans of SaaS continue to price this way, and their bottom line is not shrinking.

00:06:45:06 - 00:07:08:13

Ben Hillman

I'm underscoring its significance not because of what it is, but because of what it isn't. Ending your prices in nines is not a pricing strategy. Without a pricing strategy based on the actual value of your product, you aren't delivering what your customers want, and you're not going to lock them in for the long haul. The only pricing strategy that does this is value based pricing.

00:07:08:17 - 00:07:25:02

Vivien Shao

I'm Vivien, I'm a pricing strategist on the price intelligently team. We have worked with literally hundreds of, SaaS companies. Value-based pricing is essentially setting your pricing based off of what your customers are willing to pay. It's much more focused on your customer and your product.

00:07:25:07 - 00:07:46:10

Ben Hillman

And we know that the more successful a company is, the more likely they're using a value based pricing model. You can see here that 45% of companies with are north of $500 million are utilizing it, compared to only 20% of companies with around $1 million in error. So here's a brief overview of how to price your product based on value.

00:07:46:10 - 00:08:04:10

Ben Hillman

At the core of value based pricing is a value metric. A value metric is not only how much you charge, but what you're charging for. This could be per seat, per gigabyte of storage per canoe. All right, I'm getting out the canoe, I promise. Once you've got your value metric, next you're going to want to do some research.

00:08:04:15 - 00:08:19:01

Ben Hillman

Doing this research properly will help you avoid getting answers where people just tell you, just give it to me as cheap as possible. First, start by collecting data on your customer base, who they are, and what they get out of your product. Then use this data to determine your price point.

00:08:19:03 - 00:08:31:01

Vivien Shao

We're setting a price range based off of what is realistic in the space kind of, things that you've done in the past. It's not as simple as just like, here's a bunch of prices. Like I'll pick the lowest one.

00:08:31:03 - 00:08:49:17

Ben Hillman

You're going to want to ask questions like, at what price would this be too low that you would question the value of the product, as well as what price would be too high? Then figure out folks relative preference of what they want from a product. This is a survey that basically asks potential customers, what is the one thing that you couldn't live without

00:08:49:22 - 00:08:51:15

Ben Hillman

And the one thing you could?

00:08:51:17 - 00:09:02:08

Vivien Shao

Relative preference is really important because people don't really know how to prioritize. The pretty neutral option. You are basically forcing respondents to make a trade off.

00:09:02:13 - 00:09:25:15

Ben Hillman

Mapping all of this data onto a value matrix will help you understand what your core features are, as well as those that might just be add ons and ones that you might not actually need. And if you repeat this process on a quarterly basis, which we recommend, how customers perceive your product will be crystal clear. Once you've figured out value based pricing, you're doing more than just getting folks in the door by charging them with a nine and look.

00:09:25:21 - 00:09:32:05

Ben Hillman

You might end up with a nine based pricing, after all, but you're focused on retaining them through an honest exchange of value.

00:09:32:05 - 00:09:43:06

Vivien Shao

If their only strategy is pricing a nine, then then yes. To your point, it's pretty rudimentary. Otherwise, I think it's relatively table stakes. Like I don't think it really moves the needle one way or another.

00:09:43:07 - 00:09:56:11

Ben Hillman

I'm skimming over a lot of information here about value based pricing. I'm by no means an expert, but the price intelligently team is. And they wrote a holistic guide on how to approach it. So the next thing you should do is check that out to learn at all.