LOLA's leading the period talk

This episode might reference ProfitWell and ProfitWell Recur, which following the acquisition by Paddle is now Paddle Studios. Some information may be out of date.

Please message us at studios@paddle.com if you have any questions or comments!

This week we are going into the nearly $40-billion feminine hygiene market. A market that is full of frustrating taxes and full of opportunity. We're going to understand by looking at LOLA, what they're doing right when it comes to their pricing, pioneering itself into the D2C feminine hygiene market. Ultimately, understanding what they're doing well, and not so well, and then wrapping up all those learnings into a nice case study, so you can take those lessons and help your own monetization strategy get on the right track.

The tampon market is one of the most unregulated and unmonitored industries in the world. On top of that, women pay a tampon tax in 35 states and dozens of countries. LOLA is looking to change things up by taking on this multi-century market. LOLA's opening up the menstrual conversation, ending the tampon tax, and providing a customized product using only quality and safe ingredients. Is that enough to continue disrupting this multi-billion dollar industry?

Below are some valuable takeaways you can implement in your own business.

- Know which value propositions drive value and willingness to pay.

undefinedundefinedundefined - Utilize offers, not percentages, for longer-term discounts.

undefinedundefined - Know where to expand in terms of cross-selling and upselling.

undefined

Guess what. Women have periods.

Shocking I know, but American women will use 11 to 16 thousand tampons in their lifetime. What’s terrifying though is the tampon market is one of the most unregulated and unmonitored industries in the world. They don’t have to disclose or label ingredients, including the chemicals used to process those ingredients. That sounds ridiculous, but it gets worse. Women have to pay a tampon tax in 35 states and dozens of countries, meaning they pay an extra $150M per year in taxes for something that goes into their bodies without any regulation. Now that’s gross.

This insanity is what led Jordana Kier and Alexandra Friedman to found LOLA in 2014 to take on the multi-century tampon market. Kier and Friedman positioned LOLA to normalize the conversation around menstruation and to end the tampon tax through a product that only uses properly labeled, quality ingredients in their tampons and other feminine care products.

LOLA's success

And though LOLA is a newby in an old space, they’ve managed to succeed and really stand out among the big brands. They’ve done this through two big factors.

First up they opened a taboo conversation. Similar to companies like Billie, Kier and Friedman took conversations normally left in the shadows of doctor’s offices and pushed them to the public conscious through content and education. Their blog, The Broadcast, tackles a wide variety of feminine health issues and other topics impacting women. This advocacy led many women and their male counterparts to realize just how off the whole market was when it came to ingredients. Plus, the taboo made their brand and conversations spread as they educated the world as intended.

Being so transparent also led to the second big factor here—trust and transparency in their product. You can’t really talk about how bad the rest of the industry is without making sure your product was of the highest quality. LOLA did this exactly right with fully transparent ingredient lists and a commitment to natural quality.

Women everywhere noticed and when you throw in great branding and packaging, you’ve got a recipe for the best tampons on the market. They’re made with 100% organic cotton and don’t contain synthetic fibers, chemical additives, fragrances, dyes, GMOs, latex, or anything you wouldn't feel comfortable using—they’re the Cadillac of tampons, but at an affordable price.

Quality and transparency is quickly making LOLA a household name, and with expansion into the sexual health market, LOLA is changing the market by just focusing on being the best, which has led to an estimated valuation between $100 and $500 million dollars, and of course, thousands and thousands of happy reviews.

Going against the grain

Women have been using some sort of feminine hygiene pads, like paper, or papyrus back in the Egyptian days. Cotton or shreds of scraps, and things like that in order to basically help with their period every single month. Right now a modern woman will use something like 11,400 tampons in their entire life.

What's really frustrating about this is that there's a lot of women who don't have access to pads or tampons. You know, especially in developing worlds. There's a really good Oscar-winning short-form documentary called "Period. End of Sentence."

A social entrepreneur in India bought a pad-making machine so that they could use, I think, fabric or cotton, to create pads. And it had a huge impact on the community. Because it makes the period less of a thing each month and more manageable, rather than this thing where they have to miss school or interrupt their work and things like that.

There's also a lot of taxes placed on tampons. Whereas things like condoms, and many other personal products that don't have any taxes placed on them. And there’s a general tax in a lot of countries that's been put on tampons. Not to mention, what they’re typically made of. A quarter of all pesticides are used by cotton farmers. So there's just a lot of not so good stuff. And what LOLA did, is they basically came out and said, "Hey, we're going to use 100% percent cotton with no synthetic fibers, fragrance-free, and hypoallergenic." They rode the wave of going against a trend.

We've seen a lot of DTC brands do that really well. You think about, even something like Tesla, an electric car company. On its own it’s great, but it's also pushed all these other auto companies to move to electric. There’s a lasting impact by pushing people in that direction. This is what LOLA is doing.

Let's take a look at their pricing page and unpack some of the data from their current and prospective customers.

LOLA's pricing page

Up front

LOLA's advantage is that women, especially in the developed world, are already very consistently using tampons, pads, and other reproductive health products. And one thing that LOLA does really well right up front when you get to their pricing page, is all of the objections are right up front.

It's made with 100% organic cotton. Its pocket-sized, BPA-free plastic applicator expands in all directions to protect against leaks. It’s gynecologist approved, hypoallergenic, and it has FDA approval. There's a good stamp there.

I've talked to Jenny, my better half, who's actually a LOLA subscriber. And when she's looking at this, she says, "Yeah, of course this is better than Tampax, and it's delivered right to my door. So why wouldn't I use it on a consistent basis?"

And I think that the big takeaway for a lot of companies is to use that kind of objection right up front, especially when you're in a DTC environment where the decision cycle isn't months, like buying a piece of software. People can fragment themselves right into the category or the plan that you're trying to offer them.

One other thing that LOLA does really well, and they kind of have to, given the nature of the problem that they're solving, is they have customizable packaging to solve the user fragmentation problem. What you'll notice here is that LOLA actually gives you options based on your body, in terms of absorbency, leakage, and these types of things. What's good about it is that then you also have the options of every four or every eight weeks, depending on your cycle. Once you customize this, you basically throw it into the cart and go from there.

You notice this with a lot of products where every user is a little bit different, but they all need the product, and offering that variety and customization is another objection that allows you to get over. It also helps you with the user fragmentation problem because not all women are the same. Make it easy for people to find a customized fit, so that they don't have to think about going out and buying a variety pack where a good amount will likely go unused. Remove those types of inconveniences. It’s very really powerful because every LOLA box is unique to the woman.

Let's take a look at the data.

Data and analysis

Know which value propositions drive value and drive willingness to pay

I don't want to belabor the point, but the whole concept of 100% organic, fragrance free, no synthetic fibers, etc., is powerful. What's really powerful is not only in the pricing pages, but that they're continuing to reinforce it right there in the box about where the ingredients are. As a guy, l don't think we appreciate how crappy the materials in a lot of tampons are. LOLA's definitely leaned into it, and I think it’s a huge source of value.

What are the things that are actually going to be a backstop to purchasing, and then what are the things that are actually going to drive value? So, we actually collected willingness-to-pay data using our pricing software where we actually talked to current LOLA customers and potential LOLA customers. We asked them about the willingness to pay on a monthly basis for tampons. We then put different value propositions on top of it and measured what the relative difference is between those numbers to see which positioning and which value propositions actually drove more value.

And what you'll see here, this whole concept of “gynecologist approved,” it's table stakes. It’s good, but may help get you over the line, but it’s not necessarily adding value. But things like no chemical additives, dyes or fragrances, and 100% organic cotton, those are boosting things by 10 to 20% in terms of value.

When you're talking about a fairly commoditized product—and these are definitely more expensive than the cheapest Tampax out there—you're willing to pay for a premium, and then the entire brand is around that premium nature. Like this box, objectively, is more beautiful than some of the cartoonish boxes you see in the feminine hygiene aisle within CVS or Walgreens.

Now the other thing here, that I think LOLA's missing out on, or at least I didn't see it on the website as much as I saw it on Cora, one of their competitors, is the concept of supporting feminine hygiene abroad—a cause. It's not quite on top, but it's definitely on the main page in Cora.Time and time again, we’ve seen causes be a part of the brand in DTC.

And having that cause, as a guy, with different products that I use on a regular basis, I'm more than willing to purchase or use this because I'm already getting utility from a better product. But in addition to that, I'm helping the world be a better place, so I'm more than willing to pay more to offset that, in addition to the higher quality product.

I think as a DTC operator, if you're out there and you're thinking through this—one, really make sure you understand your value proposition. You have to collect some data to make sure that if I change up my value props or my flow, I can actually change willingness to pay, and ultimately, probably retention on the subscription side as well. But in addition to that, imbuing some sort of cause into your business. Especially if you're in a world where you have very different access to something. It's kind of an easy win, and it probably is one of those things that you're thinking of doing already. So it's not something that's too arduous.

We've talked about this before, but even if they don't do a one-for-one model, there's still the ability to add a donation to their site.They could totally support a cause. Add a dollar per month for helping folks in different regions get access to reproductive health products. And we found time and time again that it boosts not only retention, but it also boosts more purchases that come through. And LOLA is going after more than just tampons and pads as well.

Value Matrix

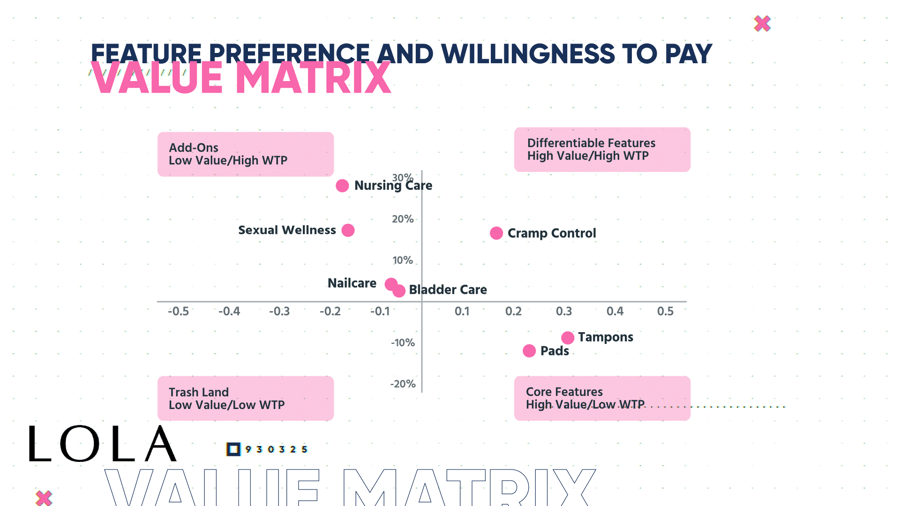

You're about to see something called a value matrix. We collected data from the group comparing feature preferences and plotted those on the horizontal axis, more valued features on the right, less valued on the left. We then collected willingness to pay for the overall product and plotted that based on their number-one feature preference on the y-axis. Analyzing data in this manner allows us to determine which features are differentiable add-ons, core, or commoditized for each segment.

Nowhere to expand in terms of cross sells and upsells?

We've talked a lot about tampons and pads, which are the table stakes for LOLA. But you can see some of the areas where they're really starting to invest, have higher willingness to pay. We talk about cramp control and sexual wellness, and these are things that their prospective customers and current customers are likely willing to pay more for, and would be great targets for cross-selling and upselling.

This world is really fascinating too, because you have FLEX Fits and Cora, who have alternatives to tampons and pads. There's the Cora cup, which is a menstrual cup. There's also FLEX Fits, a whole different way of helping with your reproductive cycle. Feminine health or female health, depending on how you want to look at it, is one of those things where—very similar to the Dollar Shave Clubs of the world, the coffee companies in the world—you want to expand across the counter or expand across the bathroom, essentially, in order to boost that overall average revenue per user, as well as your average order value.

Sexual wellness is not something that everyone's thinking about going toward, from a LOLA perspective, but the people who are, they're willing to pay about 14% more.

I think that the takeaway for a lot of DTC brands is, as you're expanding across the domain that you're in, make sure you're honing in on those things that are actually really valuable. Whereas for LOLA, things like nursing care and bladder care are really good opportunities that they're not really doing much on right now. And maybe it's not in their thesis, not in their wheelhouse, but it is something they should think about.

Utilize offers, not percentages, for longer term discounts

What we find with LOLA, and a lot of other DTC brands, is that they're not optimizing for longer term as much as they should be. And what I mean by that is locking someone into a three-month subscription, a six-month subscription, or an annual subscription. Or just in general, getting folks to upgrade or move on to something else—not with percentages, but with some sort of offer. Whereas if you tell me it's $5 off, I'm saving $5, I'm getting a month free, I'm getting an extra product in addition to the product I'm getting if I sign up for a longer term, those are things that I can pay and latch onto.

It makes that impulse decision easy for me, either in the checkout or very close to the checkout. And then all of a sudden you have an extra $5 a month, $10 a month from that particular user, or they're guaranteed across six months or 12 months.

We get so many questions like, "What are some quick things that we could do from a pricing standpoint that will help move the needle?" And I think the human psychology piece about really resonating with the human brain better, and making it easier for them to understand the value is a huge piece of low-hanging fruit that people can really take care of. I don't want to say that these are premium feminine care products, but there's some margin there to play with, I presume. You want to experiment with offsetting. If you can keep them around for like eight months, you can give up a little bit of margin on that first month or the second month or the overall, because the overall take from a profit or revenue perspective is going to be so much higher.

It's one of those things that you have to balance, but you have to be cognizant of it. And even in your sign-up offers, or in your offers when it comes to getting on a longer-term contract, you have to make sure you're doing less percentage base. It's kind of like old school retail, unless you're a discount brand, it doesn't work as well.

You gave to do more new school—dollars off actual items. And you can use old inventory or inventory that is sitting on the shelf as well. People won't be the wiser.

This world is really fascinating too, because you have FLEX Fits and Cora, who have alternatives to tampons and pads. There's the Cora cup, which is a menstrual cup. There's also FLEX Fits, a whole different way of helping with your reproductive cycle. Feminine health or female health, depending on how you want to look at it, is one of those things where—very similar to the Dollar Shave Clubs of the world, the coffee companies in the world—you want to expand across the counter or expand across the bathroom, essentially, in order to boost that overall average revenue per user, as well as your average order value.

Sexual wellness is not something that everyone's thinking about going toward, from a LOLA perspective, but the people who are, they're willing to pay about 14% more.

I think that the takeaway for a lot of DTC brands is, as you're expanding across the domain that you're in, make sure you're honing in on those things that are actually really valuable. Whereas for LOLA, things like nursing care and bladder care are really good opportunities that they're not really doing much on right now. And maybe it's not in their thesis, not in their wheelhouse, but it is something they should think about.

Utilize offers, not percentages, for longer term discounts

What we find with LOLA, and a lot of other DTC brands, is that they're not optimizing for longer term as much as they should be. And what I mean by that is locking someone into a three-month subscription, a six-month subscription, or an annual subscription. Or just in general, getting folks to upgrade or move on to something else—not with percentages, but with some sort of offer. Whereas if you tell me it's $5 off, I'm saving $5, I'm getting a month free, I'm getting an extra product in addition to the product I'm getting if I sign up for a longer term, those are things that I can pay and latch onto.

It makes that impulse decision easy for me, either in the checkout or very close to the checkout. And then all of a sudden you have an extra $5 a month, $10 a month from that particular user, or they're guaranteed across six months or 12 months.

We get so many questions like, "What are some quick things that we could do from a pricing standpoint that will help move the needle?" And I think the human psychology piece about really resonating with the human brain better, and making it easier for them to understand the value is a huge piece of low-hanging fruit that people can really take care of. I don't want to say that these are premium feminine care products, but there's some margin there to play with, I presume. You want to experiment with offsetting. If you can keep them around for like eight months, you can give up a little bit of margin on that first month or the second month or the overall, because the overall take from a profit or revenue perspective is going to be so much higher.

It's one of those things that you have to balance, but you have to be cognizant of it. And even in your sign-up offers, or in your offers when it comes to getting on a longer-term contract, you have to make sure you're doing less percentage base. It's kind of like old school retail, unless you're a discount brand, it doesn't work as well.

You gave to do more new school—dollars off actual items. And you can use old inventory or inventory that is sitting on the shelf as well. People won't be the wiser.

Recap:

- Know which value propositions drive value and willingness to pay. It's so much more crucial in DTC than it is in something like B2B. You have to understand what’s important and you need to understand the fragmented user base. You have to identify how you know them. Accentuate down the funnel, in addition to that.

- Utilize offers, not percentages, for longer term discounts. And I would even argue to add offers to sign up. We see folks like ButcherBox do this really well. They offer you free bacon for life as long as you're continuing to be a customer. BarkBox also does this really well. They have exclusive toys depending on the season that you get if you sign up for a longer-term contract. The human brain, that's just how we think. We want to get something rather than getting a percentage off, which is a little bit harder for us to understand.

- Know where to expand in terms of cross sell and upsell. Get down to the data and understand what your customers value and what they're willing to pay for. With LOLA, they have some really clear, potential features and offers that they could roll out to their customers. It would really align with what they're already offering and potentially drive expansionary revenue for them in years to come.

And there's a balance here. As an operator you can’t offer everything and anything under the sun here. I mean, you can. You can build up to that. Brands like Dollar Shave Club have done that. But I think you have to pick your spots, and collecting some data allows you to figure that out. When you see this data, you find out that there’s actually some pretty big things you can do.