More and more companies are making the switch to recurring revenue. Here's how Adobe, GoPro, Gillette, and Microsoft saved their businesses through the subscription economy.

The beauty of the subscription world is the compounding nature of the relationships. You acquire a customer, charge them for the value you're providing, and as long as you and the customer agree on that value, they'll keep paying and stick around for a long time.

Yet, the subscription world is still young with Salesforce being around for a couple of decades and Bessemer making their first cloud investment in only 1997. You may say "well, that was 20 years ago", but when you think about the millennia that retail and other industries have been around, the recurring revenue model is still an infant.

Fortunately, our little youngin' is going through the craziest growth spurt ever seen with traditional software companies and hardware companies, B2B or B2C—taking advantage of the recurring relationship economy for higher revenues, more growth, and better customers.

To better understand and learn from these transformational stories, let's look at how Adobe, GoPro, Microsoft, and Gilette have attacked their core businesses to take advantage of the subscription economy.

First though - why is the subscription world so important

It may seem obvious, but let's look at the true power of recurring revenue. While you may have to pay a larger portion upfront to acquire a customer, the beauty of the recurring revenue world is that these customers are the gifts that keep on giving.

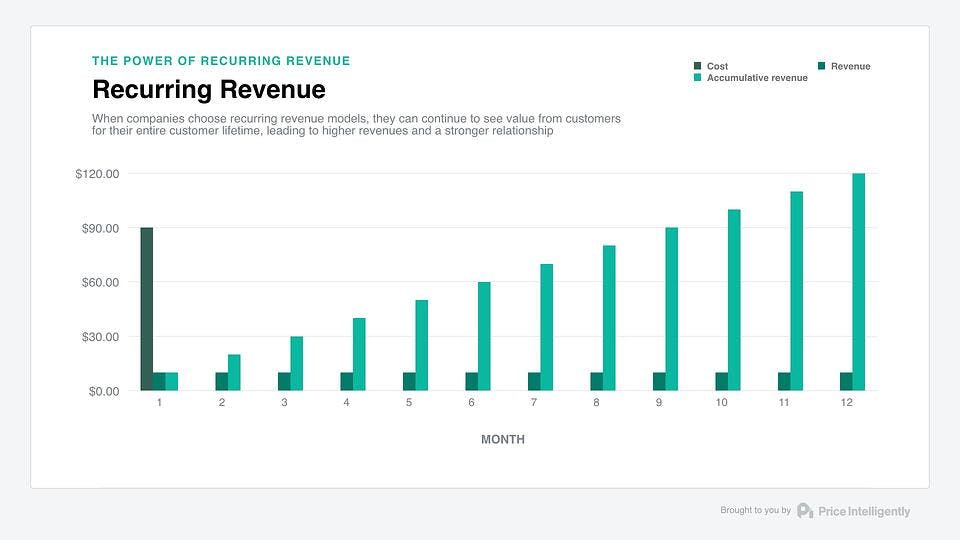

In a one-time payment model, you get results like the below, where you make a profit, but in order to make more money on a customer, you have to sell them another item.

Contrast this relationship with Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR). Now, you may have higher costs upfront (traditionally at least), but the accumulated revenue very quickly covers those costs and then starts to exceed those costs within a reasonable amount of time.

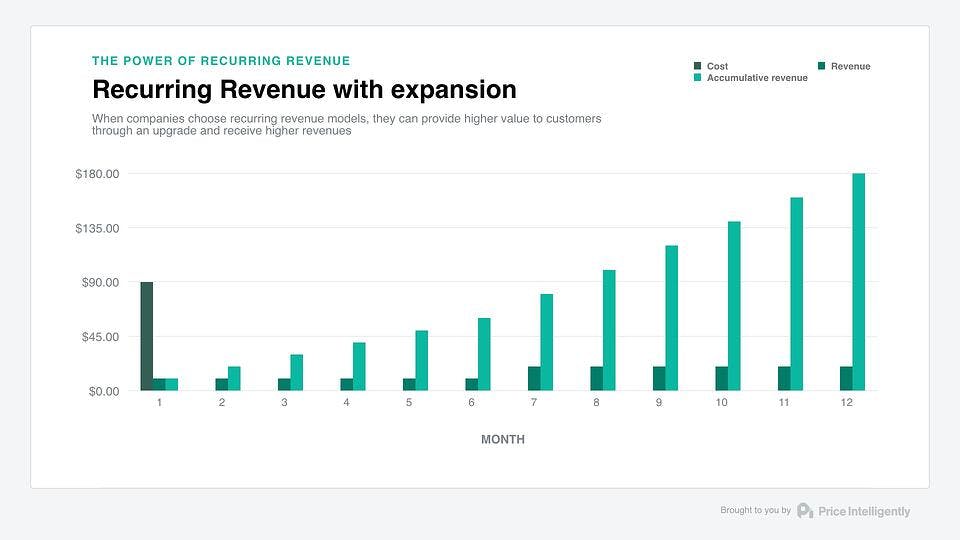

The secret (and beauty) isn't in the recurring piece necessarily, but in the relationship building, which is accounted for through good ol' expansionary revenue. If you're able to get into that particular account and essentially upsell through added value (either through more usage of your product, add-ons, etc.) you can not only recover your customer acquisition cost (CAC) quicker, but you can maximize profits, as well.

I can't stress the relationship aspect enough. While you can have a relationship in a one-time purchase scenario, the relationship isn't baked directly in the product. If someone is automatically paying you each month, consistently logging in to your product, and frequently interacting with your brand, then there shouldn't be an excuse for not winning and keeping this customer for a significant amount of time.

Put another way, your activation energy to get a customer to give you money is supremely catalyzed by the recurring revenue model. Through that relationship and catalyst you create a virtuous cycle of more touchpoints and more data for you to learn about your customer and how they interact with the product, sparking a deeper and deeper relationship.

Let's chat through some quick case studies of companies who have made a success of pivoting to subscription revenue

1. Adobe transformed after decades of perpetual software that was running out of update surface area

Adobe is perhaps the software company that took the most drastic and noticeable shift to the subscription economy.

Ever since the first Photoshop was released in 1988, Adobe customers had become accustomed to a certain business model: larger and larger downloads (or more disks, CDs, or DVDs) for ever-increasing amounts of money. The last non-Creative Cloud version of Photoshop cost $999 for over a gigabyte of photo-editing goodness.

Yet, this revenue model led to a big challenge for Adobe: it was only a one-off monetization opportunity. Yes, Adobe could get a hefty $999 from users, but only a single time for a perpetual license. Once that sum was paid, Adobe had no way to get further revenue from that individual customer unless that customer saw the new version of Photoshop as a big enough upgrade to make another purchase. If they didn't see this value, the customers were free to use the product for work and memes until the End of Days.

Adobe got around this through versioning. Every year the updates of Adobe products would get drastically better. There would be something new that digital artists had to have that would push them to update. This is an older version of the iPhone revenue model—make each new release so absolutely awesome that people want to upgrade even at a significant cost.

This model and price tag worked as long as the creative buyers were getting something substantially new with each release. Minor updates can't justify a high price, and users wouldn't upgrade to the most recent version without a comparative increase in value. This is the position Adobe is in now. Photoshop, Illustrator, et al. don't have as much room for growth. Updates are smaller.

To make the switch, Adobe took the plunge by offering Photoshop for $9.99 per month. This is 100X less than the cost of the perpetual license, but Adobe can make this up in two ways:

- More customers: With a reasonable price, more people will feel comfortable signing up.

- Longer lifetime: At 9.99, the product is extremely affordable as an entry point. Customers will stay around for a longer lifeline and since Adobe is getting those first dollar from customers, there's a bigger opportunity to expand across the entire lifetime of the customer.

The bottom line on Adobe: Adobe can get more people into their ecosystem with their lower priced subscription model. These users then provide a wider base for using more and more storage, other apps, and other Adobe products, which therein improves the lifetime value (LTV) consistently.

2. GoPro switched to build an entirely new business

GoPro isn't known for their software; they're known for their cameras and gear that allow you to take fun action shots of your dog on your hikes (let's face it, most of us aren't doing the extreme sports we see in the GoPro videos). Through fantastic marketing, they saw rapid initial growth, but their business model started to sputter.

Sure, customers will purchase a GoPro for a significant price, but they'll quickly lose interest and the expensive camera will end up in a drawer somewhere. They may buy some extra accessories, but the lifetime value starts to cap out and GoPro can't grow rapidly enough to make The Street happy.

How do we solve this problem? Well, as Zuora says - "The future of GoPro isn't products, it's services."

CEO Nick Woodman and crew released GoPro Plus Monthly to start to pad their bottom line. For $4.99 per month, you can upload and edit your GoPro footage in the cloud. Since GoPro content typically languishes on SD cards this service puts that content in the cloud whenever you attach your GoPro to the computer, meaning that you can start to experience what GoPro is all about—producing awesome, crazy videos (or at least some great mash ups of your dog).

GoPro will obviously continue to build cameras, accessories, drones, etc. Yet, the service component of their business model allows them to have two revenue streams: one-off revenue from cameras and accessories, and recurring revenue from their storage and editing app.

The bottom line on GoPro: One-time hardware or general purchases aren't the enemy. You can actually combine the two to make a beautiful ensemble of padded lifetime subscription revenue.

3. Microsoft switched to keep up with its biggest customers

If Microsoft, the mother-father-god of perpetual, desktop software is switching away from the desktop then you know something is up. The software behemoth made the change back in 2011 when they launched Office 365, which offered the same tools the regular desktop version did, but through the cloud instead.

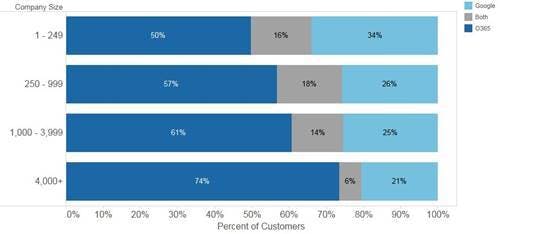

Office 365 is $9.99 per month (or $99.99 annually), which compares to the perpetual price tag of $399. Value and some of the lessons we learned by looking at Adobe might have been part of Microsoft's decision to go the recurring revenue route, but the real reason can be summed up in one word: Google.

When Google released Google Apps for Business (now G Suite), Microsoft saw that they were going after their cherished cash cow—enterprise customers.

Google's siege worked.

Companies started to shift over to Google in the cloud rather than deal with the issues of installing and managing office offline. In the current workplace, a cloud solution allows companies far more variability in their work processes.

Yet, with Office 365, Microsoft fought back and started winning:

Larger companies chose Office 365 largely because they craved the Office experience that they've had for decades at this point. While appealing from a cloud perspective, learning the new G Suite way wasn't great, so Microsoft's shift allowed customers to get the best of both worlds.The results can be seen on their balance sheet:

Office 365, by itself, saw an impressive revenue growth of nearly 70% and its consumer subscribers increased to 18.2 million, which means that in this quarter alone an impressive 3 million subscribers came on board.

4. Gillette switched to challenge the new competition

Gillette gives us what could be the biggest capitulation to the wonders of recurring revenue. When Gillette was founded, they effectively built their own business model. Allow people to buy razors for cheap, but then charge steeply for extra blades. This model worked excellently for over 100 years until subscriptions came along to usurp it.

Dollar Shave Club and then Harry's made buying razors and blades simpler, and importantly cheaper, through the recurring revenue model. Instead of $13 a time for blades, as well as a trip to the store, you could get blades for as little as $3, and delivered straight to your door.

Granted, the actual cost of the blades weren't high, so if you wanted to go through special channels you could get extremely cheap blades, but the brands of Dollar Shave Club and Harry's, along with the convenience, won over modern consumers looking for both of those pieces.

The massive success of these subscription companies hit Gillette hard. In 2016, Proctor & Gamble, the owners of the Gillette brand, saw sales for their grooming segment fall by 6 percent. Dollar Shave Club on the other hand grew like the peskiest of facial hair to the point that Unilever bought them for $1 billion in 2016.

As typical incumbents tend to act, Gillette at first went on the offensive about the quality of DSC's blades, but eventually saw the light and moved to their subscription model. What's beautiful about Gillette's shift is that when a giant incumbent finally moves to the recurring model, wonderful consumer experiences start to surface.

For instance, you can now get Gillette blades for $1 delivered to you by simply texting a number 'BLADES.' While still early, a company that built one of the most successful business models in history is now evolving again to stay afloat and get to the next level of convenience and relationship building with their customers.

Bottom line on Gillette: It's not just about the money. A huge aspect of the recurring model is convenience and brand with your customers, baking in that relationship that keeps that subscription revenue flowing.

The subscription economy is here to stay

Relationships have always been the center of good businesses, but we never had the technology to properly charge based on that relationship. With the recurring revenue world of the subscription economy, we now have that opportunity given breakthroughs in consumer sentiment and base technological infrastructure.

If you're not in the subscription space, you're missing out and need to move much quicker than you are to make sure your business survives.

If you are in the subscription space, then it's time to kick the relationship aspect of your revenue model into gear. Remember, it's not just about the compounding nature of subscription growth, it's about maintaining those solid relationship with your customers and adapting to their needs in a beautiful, profitable symbiotic relationship.